From Manuscript to Printed Word

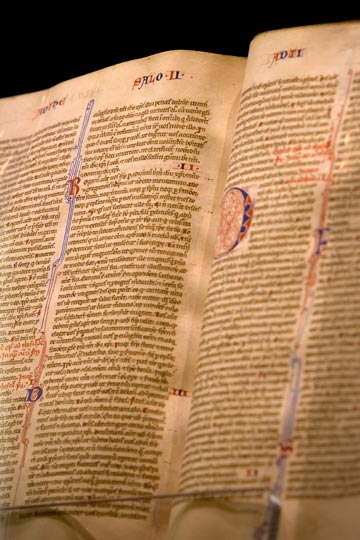

In the fifth century, St. Jerome translated the Bible into the common Latin spoken throughout the Roman Empire. This was the Vulgate or common translation. Monks and nuns in monasteries carefully copied the Bible, often taking several years to complete one manuscript. The work of the scribe was done in the monastery’s scriptorium. Many Bible manuscripts were illuminated with gold, reflecting the great value placed on the sacred Scripture (Technically, an illuminated manuscript is one with decorative gold or silver, not simply color). One scribe penned the text, leaving space for other scribes to add decorative art and rubrication, or red lettering. Bibles were expensive, and even the educated or wealthy rarely saw one. People’s knowledge of the Bible often came through the paintings, carvings, and stained glass windows of the medieval cathedrals.

This Scroll of Exodus is from the Cairo Genizah, discovered by Jewish scholar Solomon Schechter in 1892. A genizah(Hebrew for “hiding place”) is a depository for sacred Hebrew books that are no longer usable. Since the books contain God’s sacred name, they cannot be simply thrown away and are kept in the genizah. This scroll, written on parchment and dating from about 1350 A.D. is from Egypt

Manuscripts from the 12th through 15th century provide examples of different sizes and styles of medieval Biblical manuscripts and books.

This manuscript was found at the Chateau de Chacenay in the 1980s, situated in the Aube department of France. It probably came to Europe after the fall of Constantinople and was bought in the 19th century by the owners of the Chateau, who were very interested in the Middle Ages. The Dunham Bible Museum also has leafs of John 8-10 from this manuscript. Andrew Patton researched the history of the manuscript; his fascinating discoveries were given in “The Fragmentation and Digital Reconstruction of a Greek Lectionary“, a lecture at the University of Birmingham given in 2021. Patton’s research can also be found in That Nothing May be Lost: Fragments an the New Testament Text.

Scroll of Esther, Vellum, 17th century

Scroll of Esther, Vellum, 17th century

Illuminated in the 15th century Italian style, this exquisite Hebrew scroll contains 28 miniatures of the story of Queen Esther. Like written Hebrew, the story’s illustrations read from right to left. The key figures of King Xerxes, Vashti. Mordecai. Esther and Haman are shown at the appropriate locations in the story.

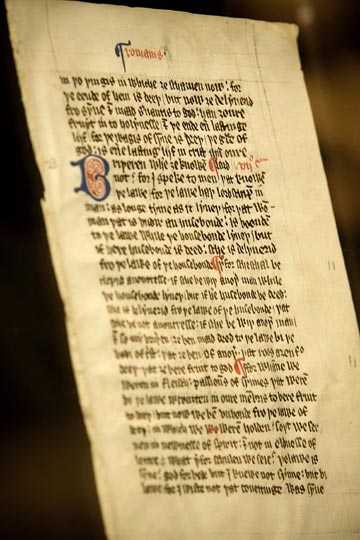

An original leaf from the 14th century of John Wycliffe’s translation of the Bible into English. Wycliffe and his followers made the first complete English translation of the Bible, translating from the Latin Vulgate. Opposition to the people having the Bible in English led to the Constitutions of Oxford in 1408, which forbade the making or reading of any portion of the Scripture in English, on penalty of forfeiting life and goods. In spite of this prohibition, there are more Wycliffe manuscripts than any other English medieval writing, indicating the hunger of the people for the Scriptures.

Salisbury Catedral, Chapter House Carvings

Though many people could not read during this period, nor could they afford a Bible, the content of the Scriptures could be learned through sermons and the stained glass windows and carvings on churches. In Salisbury Cathedral, for example, the chapter house built between 1263 and 1284, contains a frieze consisting of 60 scenes from the first books of the Bible, from the creation of the world through the Exodus from Egypt. The scenes depicted explain the foundational stories and truths of the Bible foundational to the Bible’s history: