History of the English Bible

The history of the English Bible is intimately connected with the political situation in England during the 16th and 17th centuries. Each change in monarch brought a different religious configuration to the country, and a different legal form of the Christian faith. Henry VIII was a devout Catholic who separated from the Pope over issues of his divorce. The first English Bibles were printed under his reign. His daughter Queen Mary reverted to forbidding English Bibles within the country. Under her reign, many Protestants fled to avoid persecution. When her sister Elizabeth became Queen, many Catholics similarly fled to avoid persecution.

The history of the English Bible is intimately connected with the political situation in England during the 16th and 17th centuries. Each change in monarch brought a different religious configuration to the country, and a different legal form of the Christian faith. Henry VIII was a devout Catholic who separated from the Pope over issues of his divorce. The first English Bibles were printed under his reign. His daughter Queen Mary reverted to forbidding English Bibles within the country. Under her reign, many Protestants fled to avoid persecution. When her sister Elizabeth became Queen, many Catholics similarly fled to avoid persecution.

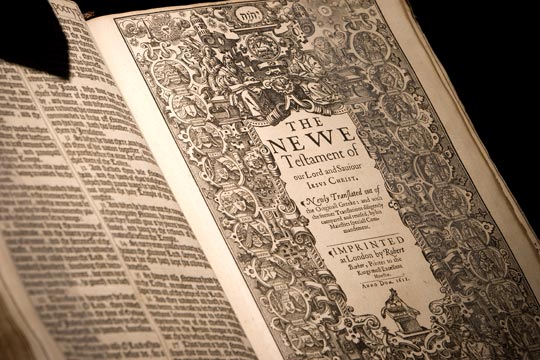

William Tyndale’s New Testament

“The Scripture is a light and shows us the true way, both what to do and what to hope – in Christ Jesus our Lord.” -William Tyndale

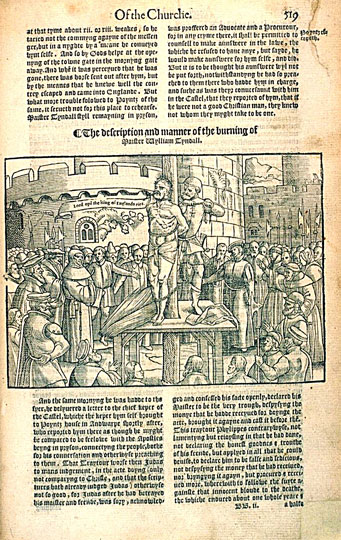

William Tyndale (1494-1536), a gifted scholar and linguist, was the first to translate the Bible into English from the original Hebrew and Greek. Tyndale wanted everyone in England, from the ploughboy to the king, to be able to read the Scripture in his own language. Since an English translation was forbidden in England, Tyndale went into exile in Europe to continue his translation work. Spies were sent to the continent to arrest Tyndale, but he remained in hiding. Copies of his New Testament translation were printed in Europe and smuggled into England. In 1535, Tyndale was betrayed to the authorities, who tried and convicted him of heresy. On October 6, 1536, Tyndale was strangled and burned at the stake. Those watching his execution heard his dying prayer, “Lord, open the King of England’s eyes.” Within months, King Henry VIII permitted a Bible in English. The first complete Bible in English was largely Tyndale’s translation. Later translations continued to be based on Tyndale; 83%of the King James Version is Tyndale’s work. Tyndale’s Bible helped shape and form the English language.

See more on William Tyndale :The Life and Legacy of William Tyndale; Fire of Devotion

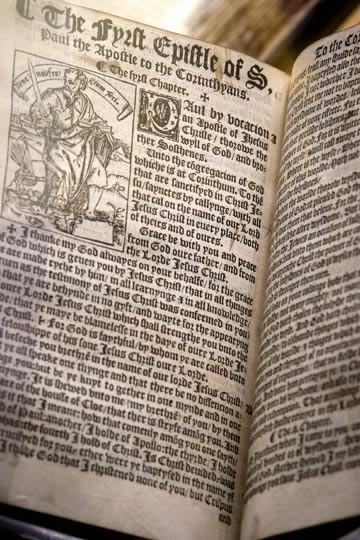

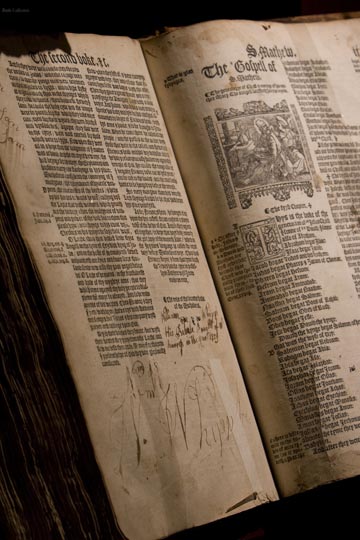

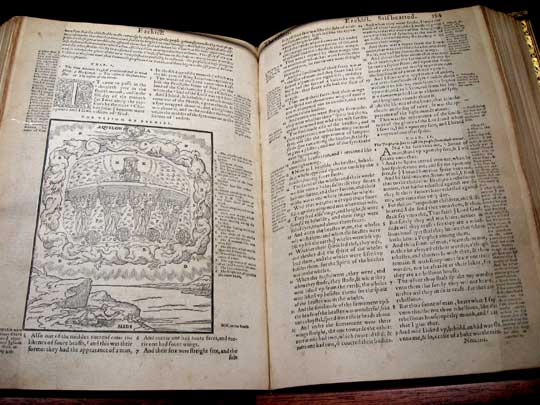

In 1526, William Tyndale’s first New Testament was printed in Europe and smuggled into England in bales of cloth. Many persons in the government and church were furious. Copies of the illegal New Testament were burned in front of St. Paul’s Cathedral in London. Tyndale’s New Testament was printed with revisions in 1535 and again in 1536. Writing of Tyndale’s English Bible translation, historian John Foxe said that it would be impossible to fully express “what a door of light they opened to the eyes of the whole English nation, which before were shut up in darkness.” The three editions printed in 1536 contain 140 original woodcut illustrations and are differentiated by the illustration of St. Paul placed before his Epistles. The illustration has St. Paul’s foot resting on a stone. In one edition the stone is blank; in another the stone bears the figure of a mole or hedgehog; and in the third the stone bears an engraver’s mark, with the initials A.B.K. The edition displayed here is the “Blank Stone” New Testament. It was printed the same year Tyndale was burned at the stake for heresy.

The first complete Bible in English was printed by Miles Coverdale in 1535. Coverdale translated Old Testament passages Tyndale had not yet translated and used Tyndale’s work for the remainder. The 1537 edition of Coverdale’s Bible was licensed by King Henry VIII and dedicated to him. The same year, John Rogers, a friend and follower of Tyndale, printed a Bible under the pseudonym of Thomas Matthews. Rogers wrote marginal notes, making this the first commentary Bible in English. Rogers was the first martyr under Queen Mary. The Matthews Bible on display in the Dunham Bible Museum once belonged to William Whipple, who signed his signature at the front of the New Testament. William Whipple was a signer of the Declaration of Independence and an officer at the Battle of Saratoga.

Both the images and Scriptures on the title page convey a definite royal message: the King had authority from God to give the Bible to the people.

Notice these features:

- At the very top of the page, overseeing all, is a very Christ-like face, depicting God. The words on the ribbons coming from God the Latin for 2 Scriptures

- “So the words also that come out of my mouth shall not return again void unto me, but shall accomplish my will.” (Isaiah 55:11)

- “I have found a man close to my own heart, which shall fulfill all my will.” (Acts 13:22)

- At the top right hand corner, facing God is King David (whose face looks very much like Henry VIII’s), with the words from Psalm 119:105, “Thy word is a lantern unto my feet”

- Central to all is the figure of King Henry VIII, whose crown has been removed in deference to God The King hands the Verbum Dei (the Word of God) to the leaders of the Church, (Thomas Cranmer, the Archbishop of Canterbury), and the Civil Government (Thomas Cromwell, the Lord Privy Seal).

- Archbishops and bishops approach Cranmer on the left, and five nobleman approach Cromwell on the right.

- To Cranmer Henry says “Such things command and teach” (I Timothy 4:11)

- To Cromwell he says, “Judge righteously; hear the small as well as the great.” (Deuteronomy 1:16-17

- To everyone Henry Says, “My commandment is, in my dominion & kingdom, that men fear and stand in awe of the living God.”

- In the left middle picture, Cranmer passes the Bible to the clergy with the words, “Feed ye Christ’s flock” (I Peter 5:2)

- On the right middle picture, Cromwell hands the Bible to the laymen saying, “Shun evil, and do good; seek peace and ensue it.”

- At the left top of the bottom frame, a preacher urges his people to pray and give thanks for their king (I Timothy 2:1-2). The congregation responds, “Long live the King.”

In his autobiography, Benjamin Franklin recounted that members of his family were Bible readers at the very beginning of the Reformation in England, when it was illegal to have an English Bible. His ancestors hid the Bible under a stool, then placed the stool on a lap and turned the stool over to read the Scriptures. The Dunham Bible Museum exhibits include a diorama of Franklin’s great, great grandfather with the Bible under the stool ready to be read.

In his autobiography, Benjamin Franklin recounted that members of his family were Bible readers at the very beginning of the Reformation in England, when it was illegal to have an English Bible. His ancestors hid the Bible under a stool, then placed the stool on a lap and turned the stool over to read the Scriptures. The Dunham Bible Museum exhibits include a diorama of Franklin’s great, great grandfather with the Bible under the stool ready to be read.

Geneva Bible,1560.

The Bible translation begun in Geneva under Queen Mary I was completed and published during the early reign of Queen Elizabeth I. It was the first English Bible to be translated entirely from the original languages of Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek. A study Bible with notes for ordinary individuals, the Geneva Bible was the first English Bible with verse divisions. It was the version used by Shakespeare and the earliest settlers in America. The Geneva Bible is sometimes called the “Breeches Bible”, since Genesis 3:7 said Adam and Eve, “knew they were naked, and they sewed fig tree leaves together and made themselves breeches.” Read the Geneva Bible’s Preface, Incomparable Treasures of the Holy Scriptures, Summe of the whole Scripture, and How to profit in reading of the Holy Scriptures.

Bishops’ Bible, 1572.

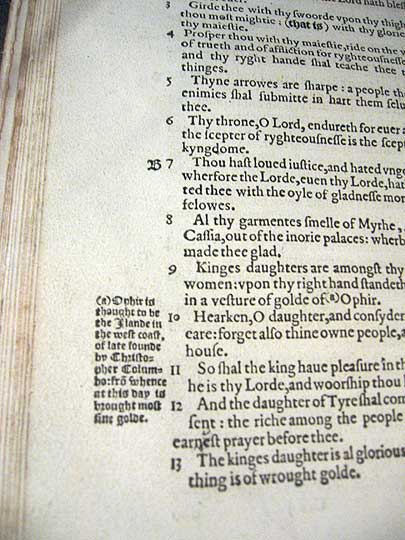

Because of the growing number of English Bible translations, Matthew Parker, archbishop of Canterbury, thought an “authorized revision” was needed. A committee of bishops revised earlier translations. The Bishops’ Bible was first published in 1568. A curious note concerning Christopher Columbus can be found in the notes for Psalm 45:9: “Ophir is thought to be the land in the west coast, of late found by Christopher Columbo: from whence at this day is brought most fine golde.”

1611 King James Bible, 1stedition, 1611.

The Bible translation commissioned by King James I owed much to earlier translators. It was the culmination of a century of English Bible production begun with William Tyndale. Mass printing allowed the Bible to be inexpensive enough to find its way into the poorest homes throughout England and later the American frontier. The King James Bible shaped the character of the English language and left an even deeper mark on the character and spiritual history of both England and America.

Apocrypha

Many of the early Bibles included “Apocryphal” books, often placed between the Old and New Testaments, These were books not in the original Hebrew Bible, but included in the Septuagint (third century B.C. Greek translation of the Old Testament). Roman Catholicism accepts the Apocrypha as part of the Scriptures. Protestants do not accept these books as divinely inspired, but they believe they have historical or moral value, even if only as historical fiction. In the original King James Bible, these books were printed as an appendix at the end of the Old Testament. Some later Protestant Bibles included them, but printed them in a smaller and different type tp show they were not a part of the inspired Scripture.

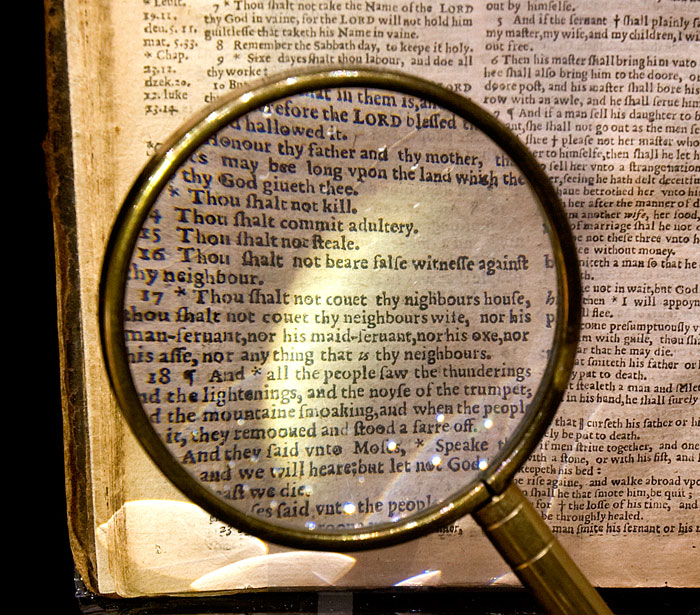

The Wicked Bible, 1631 This printing of the King James Bible is called the “Wicked Bible” because the word “not” was omitted from the seventh commandment in Exodus 20:14. The printers were fined £300 (a year’s wages) for allowing the error to get into the printing, and they were ordered to destroy the entire printing of 1000 copies. Only 11 of these rare Bibles are known to exist today.

The Wicked Bible, 1631 This printing of the King James Bible is called the “Wicked Bible” because the word “not” was omitted from the seventh commandment in Exodus 20:14. The printers were fined £300 (a year’s wages) for allowing the error to get into the printing, and they were ordered to destroy the entire printing of 1000 copies. Only 11 of these rare Bibles are known to exist today.

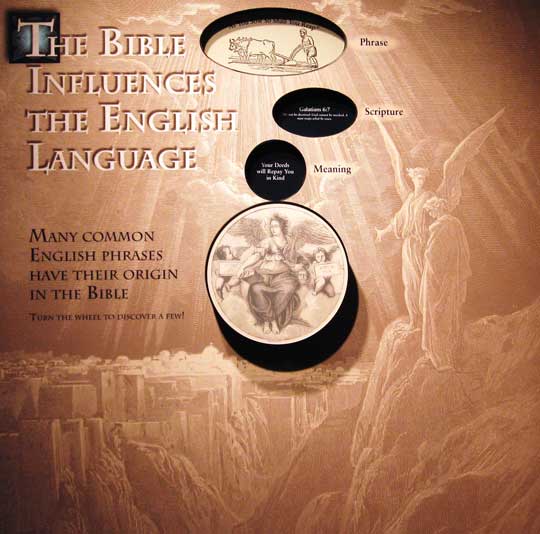

Many phrases came into the English language from the Bible. The Dunham Bible Museum exhibit includes a word wheel which illustrates a few of those phrases.

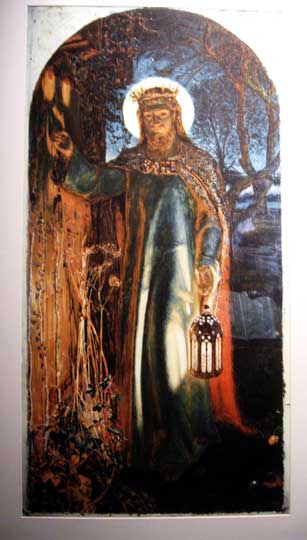

Jesus the Light of the World, print of William Holman Hunt painting, 1851.

This was one of the most well-known religious paintings in 19th century England and America, Hunt painted three copies. One is in St. Paul ’s Cathedral; another is in Keble Chapel Oxford. Rich in symbolism, the painting shows Jesus, crowned with a crown of thorns and a crown of glory, knocking at the door of the human soul. The door has been closed for some time and is overgrown with weeds. A bat, a creature of darkness and symbolizing ignorance, hangs near the door, which only can be opened from the inside. Scriptures upon which Hunt based his painting include the following:

- “Behold, I stand at the door and knock, if anyone hears My voice and opens the door, I will come in to him and dine with him, and he with Me.”Revelation 3:20

- “Jesus spoke to them again, saying, “I am the light of the world. He who follows Me shall not walk in darkness, but have the light of life.” John 8:12

- “Your word is a lamp to my feet and a light to my path.”Psalm 119:105

- “The night is far spent, the day is at hand. Therefore let us cast off the works of darkness, and let us put on the armor of light.” Romans 13:12